A friend recently told me a story of darting frantically around the tables at her oldest son’s wedding reception, looking for a place. Seating had not been assigned, and couples had filled up the formal tables. Since she is a widow, finding a single empty chair was not easy. Eventually a happy accommodation was made, but imagine the indignity of being the mother of the groom with no place to sit at the wedding dinner.

One of the most honored people at the banquet, with no place at the table.

It reminds me of our bishop after he was so unceremoniously turned out of his diocese. At a time when he should be honored for his long service, pastoral kindness, and courageous warnings about the open firehose of evil… he was ripped away from his position and his flock, and flung out like the lowliest dishwasher.

One of the most highly esteemed men in the Church, with no place at the table.

Now we have no bishop who joins us as part of our family, though we have functionaries who fulfill the administrative duties of a bishop. No one has descended to touch our grief or bind up the wounds that must be healed to restore this local church. It’s like nothing ever went amiss, and as any survivor of abuse can tell you, that is not the path to recovery.

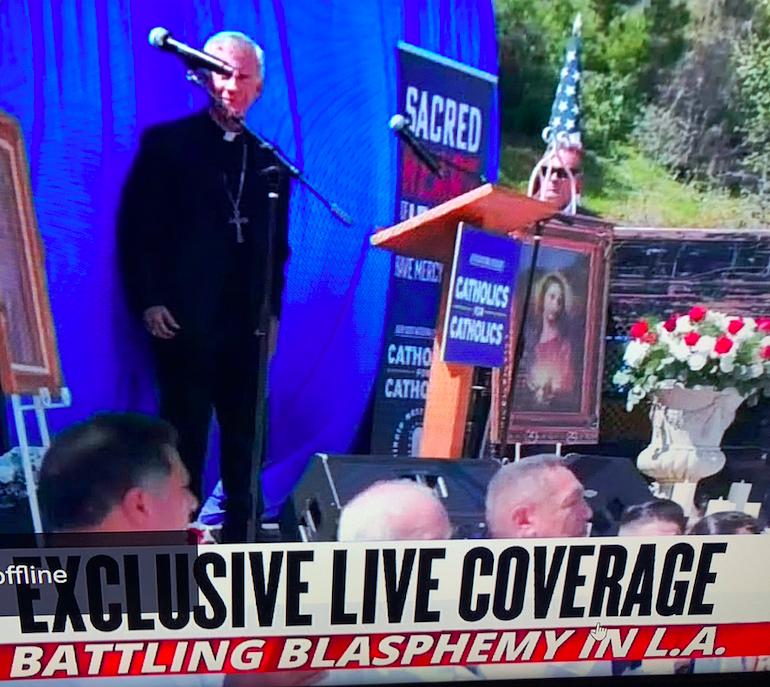

Our bishop now travels, bringing the Gospel and hope to people throughout the country, and the world. The Catholic laity is so starved for someone in authority to preach Jesus Christ Crucified, that Strickland has been adopted by the millions who are left shepherd-less when their bishops refuse to stand up to the wolves.

Our bishop is living the best life possible for an apostle of the Church without a see, but his calling is to be a shepherd. That implies a flock. Not an audience, but a flock. The modern Church has forgotten that there is a relationship between shepherds and their sheep. He knows the sheep, and the sheep know his voice. The place of a shepherd can’t be filled by an anonymity.

The laity is in danger without a shepherd. Those bishops who have spiritually abandoned their posts – and that is the great majority of them in Western society – have a stern accounting in their future. But that is no comfort to us now, as we confront the Culture of Death and Disorder on our own. We need our shepherd, the one who rebukes the wolves and fortifies the gates, not just one who signs decrees.

On Tuesday of Holy Week three years ago, the Firehouse moving van pulled away, leaving me and my household goods in Tyler, where I knew exactly no one. Disorienting as it was, I was looking forward to beginning the Triduum at the Cathedral, where I assumed the bishop I so admired would be preaching, so I could hear for myself whether he was all I’d gathered from a distance.

Two days later, on Holy Thursday evening, Bishop Strickland stood in the breezeway of the Cathedral, vested for Mass, and welcoming worshippers. He shook my hand and wished me well, on his way to the next person, but I was happily stunned. All I wanted was to hear his words; I did not expect to meet the man.

And his preaching did not disappoint. In his bilingual homily, he slipped from English to Spanish easily, with a Piney Woods twang in both, delivering a message he clearly felt with all his heart. His whole body practically vibrated with the force of his words.

Holy Thursday has always been my favorite liturgy of the year. That first year in Tyler, it was packed with the hope that I might have finally come “home,” after so many years languishing in parishes with no spiritual leadership, more social clubs than churches, and not even very good ones, at that.

Since then, our bishop has shown himself a true shepherd. He has gone to considerable trouble to attend our events and talk to all the laity gathered, even to the hundreds. He knows his sheep, and even more remarkably, he wants to know his sheep. Never have I seen a trace of that attitude we know so well from other clerics, the impatience at having to herd cats. Troublesome cats, needy cats.

Rivers don’t flow backward, so I have had little hope of our bishop being restored to us. Nevertheless, I have begun to pray that he will be. Only God knows the plans He has for Joseph Strickland, but since the removal was unjust and intemperate, I pray that the wrong may be righted.

For our bishop to be treated badly in return for good service is maddening. But for Bishop Strickland, it is a share in the degradation of the Cross. By rights, he should occupy a high place; instead, he has no place. He is Simon the Cyrenean, shouldering the Cross with Jesus. Think of the comfort Our Lord draws from his obedient son suffering without complaint! To the extent I can prayerfully, willingly, patiently endure my own sadness and anger at the loss, I participate in a minor way.

But, dear Lord, we do miss our bishop at the table. As we celebrate the priesthood on Holy Thursday, we will have to face a cathedra with no seal. I can’t picture it without sorrow. This Holy Week, we have a true Via Dolorosa to offer in union with Christ.

May God make it fruitful.